Brand Architecture Primer: Branded Houses Are Dying Out

David Aaker (pictured) has been very prolific: Brand Identity Model, Brand Equity Model, Brand Relationship Spectrum… Here, we look at his Brand Relationship Spectrum.

This is a stand-alone piece on Brand Architecture but it is also a "primer" for the post on the worst brand architecture you've ever come across:

Brand Architecture: The What

David Aaker (pictured) has been very prolific: Brand Identity Model, Brand Equity Model, Brand Relationship Spectrum… almost every key concept in brand management, he’d written something influential on it.

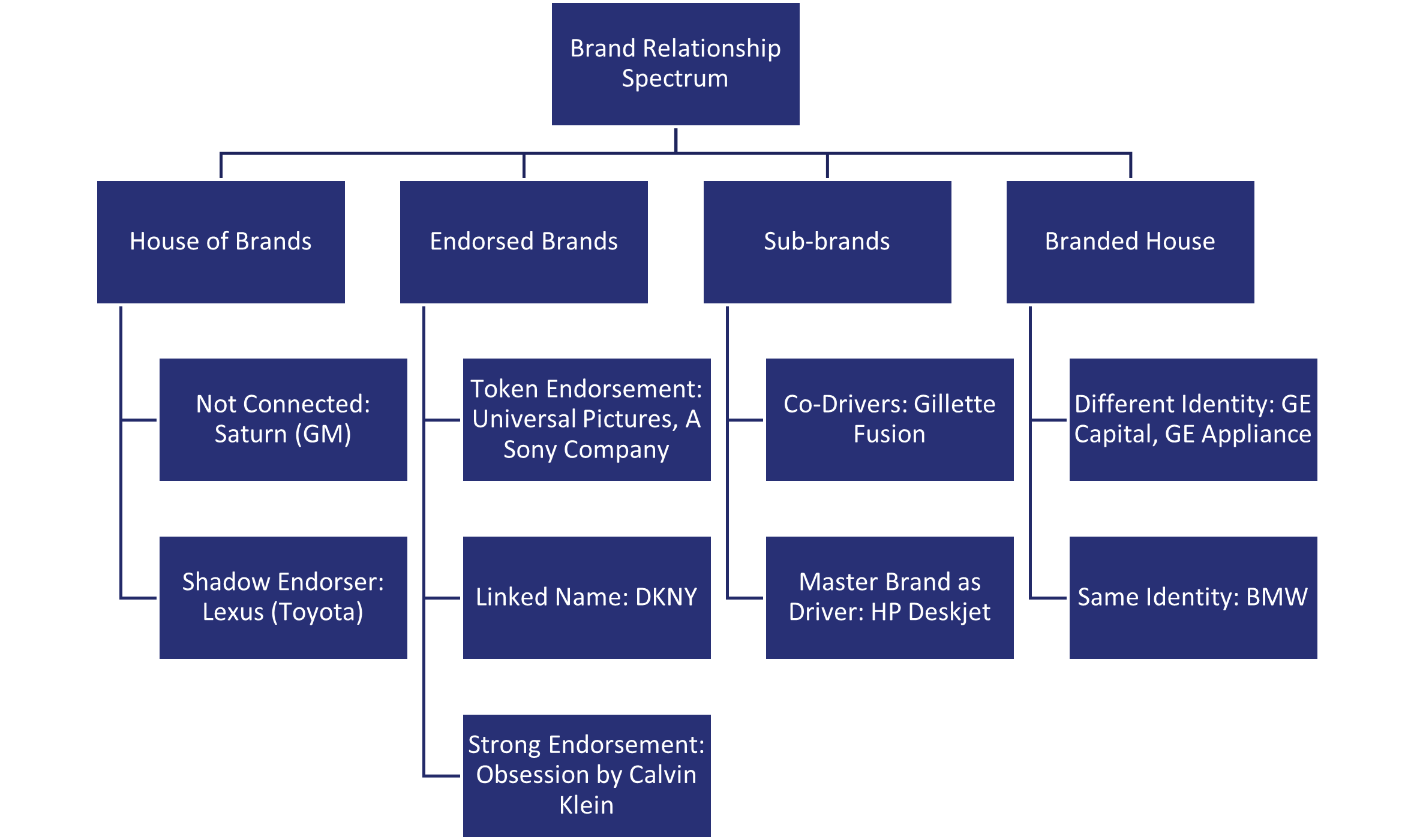

Brand Relationship Spectrum is a taxonomy of brand architecture, and it looks like this:

In the past few decades, there has been a global trend to killing(!!) brands by the firms that used to launch them, with extremely positive financial results:

- When A.G. Lafley of P&G announced in early August 2014 that Procter & Gamble would shed 100 brands (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-08-01/p-g-plans-to-shed-100-brands-to-focus-on-top-performers?sref=2hVtdgVG) the market reacted extremely positively—see Figure 2: P&G share price 2014 (source: Yahoo! Finance)

- When Alan Mulally took over Ford in 2006, Ford had a portfolio of underperforming brands (incl. Ford, Aston Martin, Land Rover, Jaguar, Volvo) and posted a loss of ~$12B. Mulally divested nearly every brand while executing his “One Ford” plan. When Mulally stepped down in 2014, Ford was posting a profit of ~$11B (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/F/ford-motor/net-income)

- If one were to compare the Fortune 500 top consumer firms lists from 1990 and 2020, one would see the change from (predominantly) Houses of Brands part of the spectrum in 1990 towards (predominantly) Branded Houses in 2020

In short: Houses of Brands are dying out, Branded Houses are on the rise, and there are reasons for this.

Brand Consolidation: The Why

No, I don’t think starting with the Why should be a thing, that’s why I started with the What. But at some stage, we must face the question: Why do I care? Especially if I’m trying to make a claim that brand consolidation is what you need.

Answer (as teased above): in most situations, a Branded House makes way more sense in many critical ways, including but not limited to:

Bigger Bang for Your Marketing Buck: Stronger ROI on Any Brand Investment

Suppose you have a marketing budget of $10m. And you have 10 brands. And they are not joined in any way, i.e. there’s no overarching endorser brand. That was Ford in 2006, and Freightways now. Every brand gets $1m on average.

Now you kill 9 of the 10 brands off.

What can your remaining brand do with the $10m budget that it couldn’t do with $1m?

When Ford sold off Jaguar, Land Rover, Volvo, and Aston Martin, its corporate investment into the Ford brand paid off multiple times through the halo effect on all its remaining sub-brands like Focus, Fiesta, Mustang and others.

And I don’t just mean promotions, though I hinted at it in this example. I mean any investment in any interaction with the customer, be it pricing, customer service, or any other experience.

Now, this is actually more of an outcome, related to the next two points…

Clarity for the Customers

The plethora of brands that all do more or less the same thing also confuses the fuck out of customers.

Why does this matter?

Well, apart from wasting a huge amount of money promoting unrelated brands, that is?

Because you’re also losing the opportunity to grow your brand equity by being top-of-mind with your customers. If they need your services in a slightly adjacent market, you are doing them and your own firm a disservice by forcing them to search for alternatives.

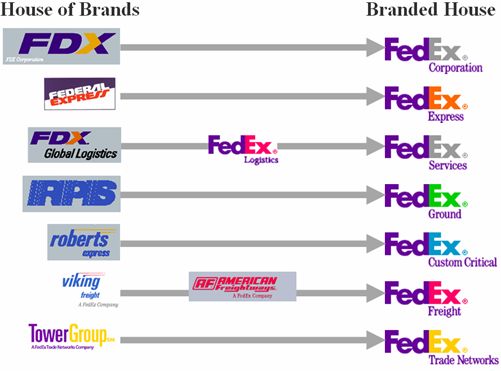

Here’s an express package delivery service example: what’s the difference between Federal Express and Roberts Express when considering a package delivery in the ’90s? Or, indeed, what’s the similarity? As evidenced in Figure 3: FedEx changing its architecture, both are now FedEx, with different customer segment/purpose focus. FedEx Custom Critical also tells the customer much more than Roberts Express, and much more clearly.

Park for later the thought of FedEx journey from the House of Brands in late 1990s to the Branded House in 2000, and its subsequent share price increase (see the period after 2000 to before the GFC in Figure 4: FedEx share price).

Clarity for the Organization

Am I saying its share price increase is due to the change in its brand architecture? Of course not! A share price is an outcome metric that is driven by a complex system, and there is no one single root cause of what’s driving it.

Ditto for performance, in general.

Having said all that, there is no reason to overly complicate an architecture of an otherwise straightforward set of offerings, like a FedEx set of brands, or Ford cars.

Clarity of brand architecture helps internally to align the organization without distracting the management. This is generally a very good thing.

It is also a signal to the market that the management knows how to manage brands, and by extension that they know what they are doing, overall.

Rarely House of Brands?

There are, in fact, reasons why a House of Brands would make sense. Or any other place on the Figure 1: Aaker's Brand Relationship Spectrum.

I won’t get into them, though suffice it to say that such discussions should always start with the same old things: the customer, the competition, and the internal view, all ultimately culminating in the financials.

When considering a multi-brand strategy, there’s no better place to start than the customer, competition, internal & financial conditions on when to launch a fighter brand, from Mark Ritson, via HBR:

But for the purposes of this discussion, we’ve already shown that there’s a bias towards fewer brands, not more, from the people who understand brand management—I put both my brand management professors squarely into this category; the market put FedEx and Ford into this category, too.

Shooting yourself in the foot

Which brings me to Freightways. I’ve taken the liberty to translate Our Brands website into a brand org chart (Figure 5: Freightways brand portfolio)—and it’s objectively nuts!

Read this: